(9) Silencieux, invisible, intangible et pourtant omniprésent en toute construction : voici quelques-uns des caractères saillants inhérents à l’espace qui, à l’échelle de l’univers physique, est « l’étendue illimitée en laquelle tout est situé ».

(10) L’espace et ses caractères sont aussi perceptibles dans le continuum matière-énergie de l’univers physique et dans les systèmes physiques et conceptuels inhérents à l’être humain, qui comprend trois relations – matière-énergie, corps-esprit et sujet-objet.

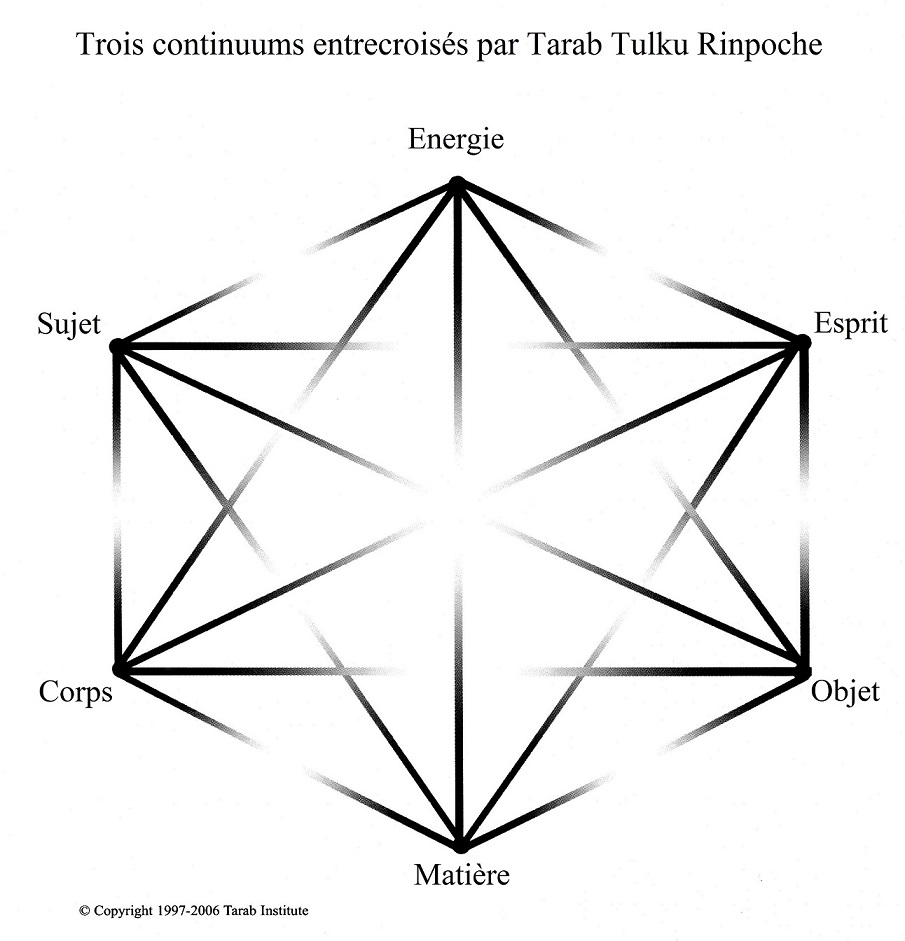

(11) La tradition indo-tibétaine, illustrée par Tarab Tulku Rinpoche XI[fr1], suggère un parallèle entre le continuum matière-énergie de l’univers et les systèmes physiques et psychologiques interdépendants inhérents à l’être humain. Ceux-ci se manifestent dans trois continuums qui s’interconnectent :

Figure 1 bis. Trois continuums entrecroisés tels que proposés par

Tarab Tulku Rinpoche [fr2] [élargir]

“D’après la métaphysique tibétaine, la matière émerge de [...] ‘l’énergie’ [...] de manière à ce que l’énergie soit la base de la matière tout en s’y répandant continuellement. Grâce à cette ressource en énergie, toutes les formes apparaissent et disparaissent [...] dans un mouvement continu de naissance, d’existence et de mort [...]. [...] on peut interpréter l’interconnexion entre corps et esprit, ainsi que celle entre sujet et objet, à travers cette interrelation entre matière et énergie. Nos corps solides sont inséparables de l’énergie basique que l’on constitue nous-mêmes et qui permet aussi le développement de notre esprit [...]”[fr3]

Si on transpose ces principes du continuum matière-énergie du plan universel vers un plan humain, une partie de ces ‘ressources d’énergie’ innées à un être humain contient le potentiel de toutes les formes d’expression. Ce fondement du potentiel expressif peut être étendu à la création de gestes dans le son acousmatique, où le déploiement de l’énergie sur un plan tangible se fait grâce à la trace auditive laissée par la morphogénèse du geste.[fr4] De plus, si on considère que cette énergie imprègne toutes les formes imaginables, les possibilités de gestes ne sont pas limitées à l’articulation de modèles sonores et non-sonores, puisque le geste est l’objet : ces possibilités sont gérées par l’imagination du sujet – ici, du compositeur –, comprise comme une expression de l’esprit. Selon ce point de vue, la perspective énergétique, à laquelle on accède au travers du sujet, permet au geste d’être créé en tant qu’expression débridée de l’imagination, facilitant ainsi une approche sans entrave du transfert des idées musicales et extramusicales du compositeur sur la toile acousmatique.

(12) L’énergie et la matière s’intègrent et s’identifient à l’espace dans la mesure où il est difficile de comprendre ou de définir ces deux termes sans y inclure la notion d’espace. De manière réciproque, l’espace devient ‘tangible’ et vivant à travers l’énergie et la matière.

(13) Ma sensibilité personnelle pour la dissémination de l’espace trouve son origine dans un intérêt général pour la dialectique, en particulier en ce qui concerne la relation entre l’univers physique et l’être humain. Cependant, à travers la composition, j’ai découvert une dialectique spatiale duelle : l’espace donne un cadre à des formes immédiatement et éternellement malléables, en permettant la naissance, et se trouve simultanément présent dans l’illimité et l’intimité. Bachelard avait déjà exprimé une vision similaire à propos de la seconde dialectique dans une perspective humaine, qu’il définit comme une ‘immensité intime’.

(14) Si le concept d’immensité relève de l’imagination humaine, on comprend comment l’espace peut être imaginé de l’échelle humaine à l’échelle de l’infini. Un retour sur les principes des gestes sonores en musique acousmatique corrobore ce point de vue en ce qui concerne les capacités de l’imagination humaine. Cependant, si l’on considère l’espace avant les gestes sonores, les possibilités de conception spatiale ne sont pas nécessairement soumises à l’impression spatiale résultant de l’articulation de gestes sonores, puisque l’espace est considéré comme l’objet. C’est alors la conception spatiale qui mène et définit les gestes sonores, étant donné que l’espace est géré par la capacité imaginative du sujet – compositeur.

[fr1] Tarab Tulku Rinpoche XI, (1934 – 2004) était un érudit Tibétain et un lama, la onzième incarnation de la lignée de Tarab Tulku. Il a fait ses études à la Drepung Monastic University au Tibet, où il a reçu un Lharampa Geshe (doctorat en philosophie et psychologie bouddhiste). Sa thèse, Science of Mind, fondée sur l’extraction de principes universels tirés des Sutras et Tantras – principes de la connaissance indo-tibétaine antique –, cherche à rendre ces concepts accessibles à la société moderne. Cette partie de sa recherche, entre autres, est publiée dans son livre Unity in Diversity (traduite par lui-même de l’allemand Einheit in der Vielfalt) (Tarab Institute, 2010).

[fr2] (Tarab Institute, 2010).

[fr3] (Tarab Institute, 2010). Tarab Tulku a développé ces concepts en se concentrant sur l’idée d’interrelation (Tendrel dans la tradition indo-tibétaine). Il a présenté ses recherches à l’International Congress of Science and the Humanities : Tendrel – Unity in Duality Conference à Munich (Allemagne) en octobre 2002, puis les a développées dans Einheit in der Vielfalt (Tarab Institute, 2010).

[fr4] Bien qu’une trace auditive résulte d’un geste physique, pour des raisons discursives, le terme « geste » désignera un geste sonore.