(15) Le rôle de l’espace dans les quatre conduites d’écoute

2. The Role of Space in the Four Reception Behaviors (15)

(16) Les propriétés sonores

2.1. Sonic properties (16)

(17) Le son est une énergie acoustique qui forme une impression spatiale grâce à la matérialité de la trace auditive. En ce qui concerne le son acousmatique, l’impression est liée aux deux éléments engendrés par cette trace : l’élément physique, ou espace tridimensionnel, lieu du mouvement et de la distribution, et l’espace spectral.

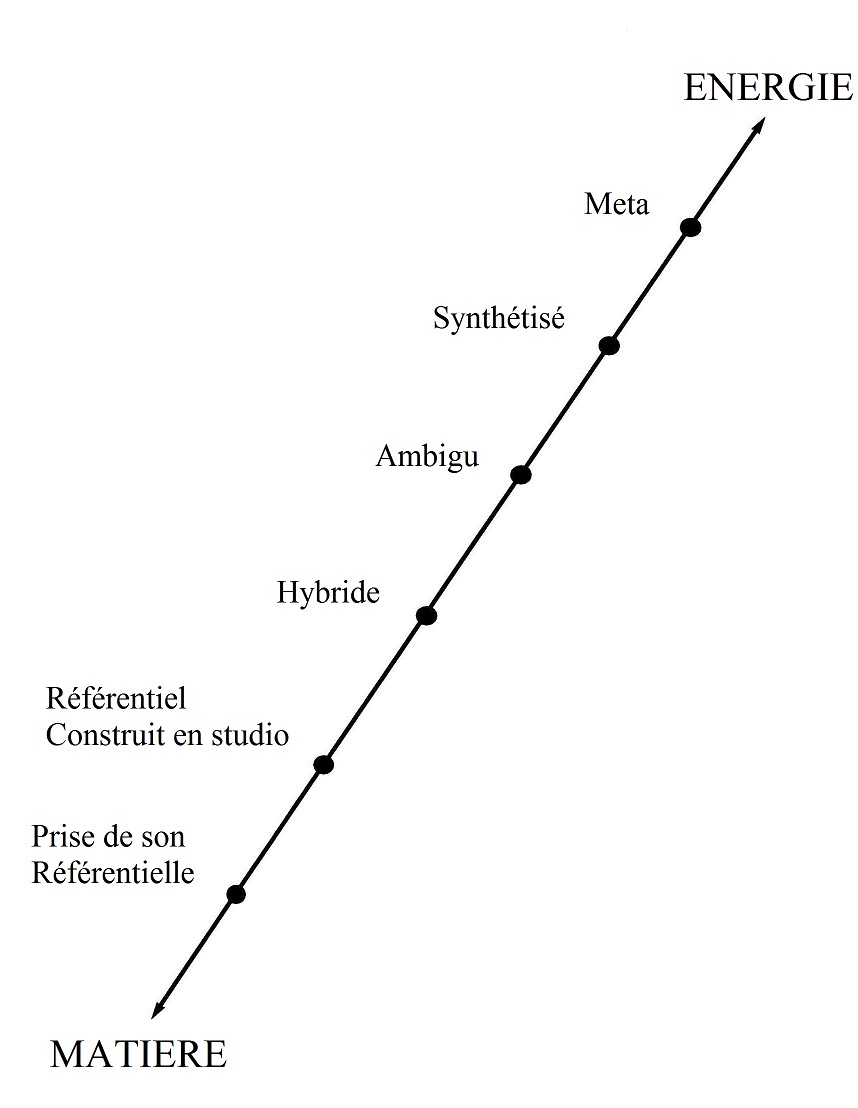

Figure 2. Le geste sur le continuum matière-énergie. [élargir]

In the previous section, I explained how energy and matter offer a window of observation for spatial occupancy insofar as their internal interconnectedness and dimensions structure and ‘claim’ space as part of their identity. Sound is acoustic energy and it dictates spatial impression through the materiality of the aural trace. In acousmatic sound, spatial impression is linked to two elements engendered by the aural trace: physical, otherwise known as three-dimensional, space, in which spatial motion and distribution occur, and spectral space. (17) Although three-dimensional space and spectral space are different entities, the two are related as they function in tandem regarding recognisability of gesture-types. Therefore, to explore the relationship between space and acousmatic sound, it is necessary to return, initially, to the Matter-Energy continuum for gesture-types and to the definition of spectral space.

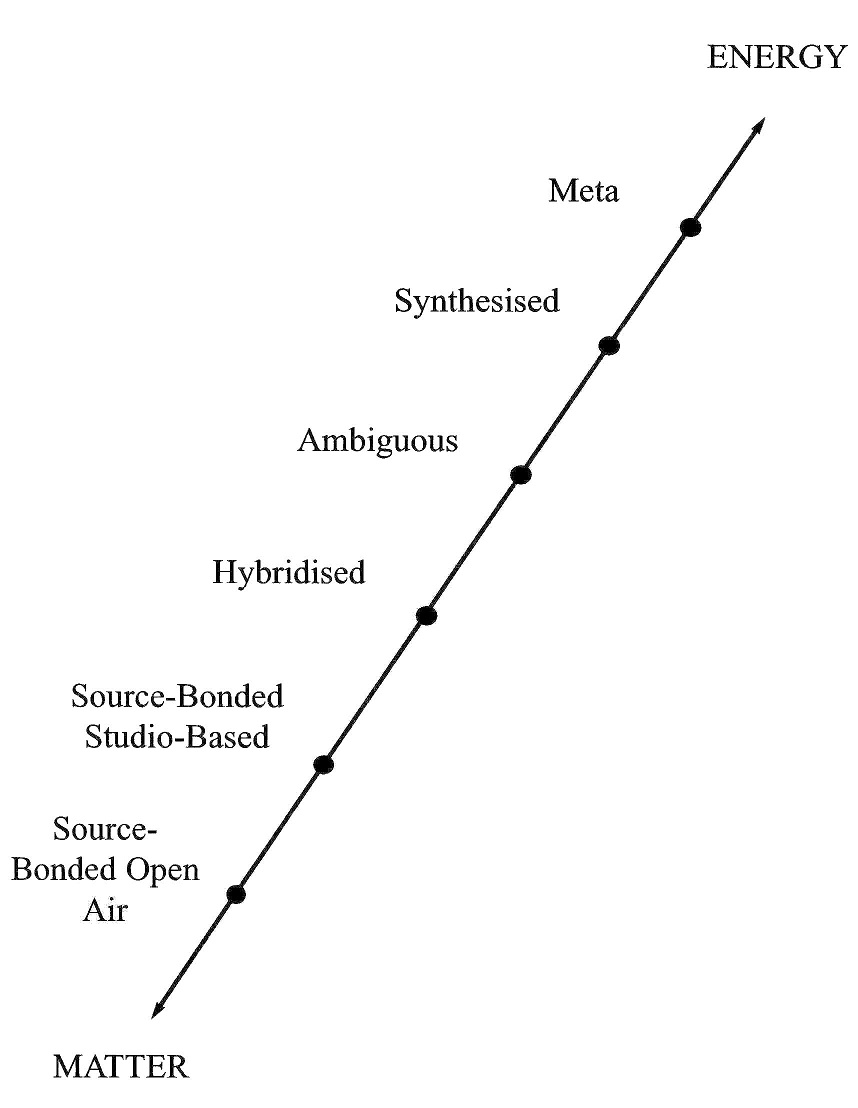

Figure 2. Gesture seen through the Matter-Energy continuum [enlarge]

(18) Le compositeur de musique acousmatique créé des gestes et les manipule via leur trace aurale tangible. La figure 2 montre des types de gestes spécifiques sur le continuum Matière-Énergie dans la perspective de la matière et de l’énergie. La matérialité de l’enregistrement d’origine est liée à la « matière ». Les qualités spectromorphologiques retravaillées, inhérentes à un méta-son, forme construite et perçue à une échelle environnementale, sont liées à l’ « énergie ». Les six catégories du continuum sont la prise de son référentielle, le son référentiel construit en studio, le son hybride, le son ambigu, le son synthétisé et le méta-son. Ces catégories illustrent une évolution d’un type d’expression gesturale qui s’exprime en spectromorphologies dense et matérielle (souvent associée aux enregistrements d’origine) vers une expression pour laquelle la matière s’efface, laissant sa place à l’énergie. Les dernières catégories présentent des spectromorphologies moins tangibles, plus énergétiques, associées avec des sons transformés, synthétisés et des méta-sons. Différents types d’impressions spatiales sont associés avec des sons dans chacune de ces catégories de manière à former la définition des catégories.

The acousmatic composer creates and works with gesture through the tangibility of its aural trace. Figure 2 exhibits specific gesture-types viewed through the Matter-Energy continuum from the perspective of matter and energy. The materiality of the source recording relates to ‘matter’. The revised spectromorphological qualities inherent in a meta-sound, a form that is constructed and perceived on an environmental scale, relate to ‘energy’. The six categories in the continuum are source-bonded open-air, source-bonded studio-based, hybridised, ambiguous, synthesised, and meta. These categories illustrate an evolution from a type of gestural expression that translates into dense and matter-oriented spectromorphologies (frequently associated with source recordings) to expressions where matter is thinned out, yielding to energy. The latter categories spawn more intangible and energy-oriented spectromorphologies associated with transformed, synthesised, and meta-sounds. Different types of spatial impression are associated with sounds in each of the categories to the extent that they help to define the categories. (18) For example, source-bonded sounds have very precise encoded spatial associations that aid the listener to define source-bondedness, whether the recording takes place in open-air or the studio. Wishart proposes that this is because “[…] any sort of live recording will carry with it information about the overall acoustic properties of the environment in which it is recorded” (Wishart, 1986: 45). In contrast, the deliberately articulated spatial dimensions in a meta-sound unfold on a vast scale, and include as much spatial detail in the foreground as in the background. However, this does not imply that evolution away from source-bondedness translates, automatically, into vast, complex, distant, or even vague spatial associations. Indeed, as we shall see, hybridised, ambiguous and synthetic sounds can have definite spatial associations whether small or large-scale, the parameters of which are different than those for source-bonded sounds.

(19) Le terme « spectre sonore » se réfère à la distribution de l’énergie acoustique, en fonction de la fréquence, dans la trace auditive. Ainsi le spectre sonore peut impliquer un axe spatial vertical. De plus, l’évolution des paramètres spectraux est liée à l’évolution des types de gestes sur le continuum énergie-matière.

(20) Puisque l’espace spectral est rattaché à l’espace tridimensionnel, une transformation qui agit sur le spectre d’un son influencera la manière dont ce son est perçu dans l’espace tridimensionnel, et une transformation qui agit sur l’espace tridimensionnel d’un son influencera la manière dont le spectre de ce son est perçu.

As previously discussed, the term sound spectra refers to the distribution of acoustic energy as a function of frequency within the aural trace. Thus, sound spectra may imply a vertical spatial axis. Further, the evolution of spectral parameters also correlates with the evolution of gesture-types on the energy-matter continuum. (19)

At this point one could query the importance of the relationship between three-dimensional space and spectral space. If sound spectra imply a vertical spatial axis, they can be seen to occupy bi-dimensional space. The listener perceives three-dimensional spatial motion and distribution in sound through acoustic energy in the form of sound spectra, which (1) have an intrinsic frequency profile that may or may not evolve over time, and (2) exist as a physically static or mobile auditory phenomenon in wide-ranging three-dimensional settings. Since spectral space is bound to three-dimensional space, it follows that any transformation that acts on a sound’s spectrum will impinge upon the manner in which it is perceived in three-dimensional space, and any transformation that acts on a sound’s three-dimensional space will impinge on the perception of its spectrum. (20) Thus, for the purpose of analysis, selected parts of works in my composition folio will be examined using two methods: (1) three-dimensional space will be rendered in terms of spatial motion and distribution; (2) the occupancy of spectral space will be scored over time. In this way, it will be possible to observe how three-dimensional space can collude with spectral space.