It is time to put to the test the sound idea that has so far been constructed at a desk and with all the means available for the study of harmonic and rhythmic dimensions. But sound, especially when it comes to the complex sound of spectral (and post-spectral) poetics, is constructed live, with your own musicians. Here, finally, a whole series of other issues relating to timbral and dynamic balances come into play. Of course, the first phase dedicated to fine-tuning the primary parameters can take some time, but with today's instrumentalists, you get to actually building up the required sound relatively quickly.

Video 3. “Discussions and friendship with Gérard Grisey (Interview Pierre-André Valade, 2/11)”, 4:23

(https://youtu.be/bVLYrrUttm0?t=263, 19/11/2022).

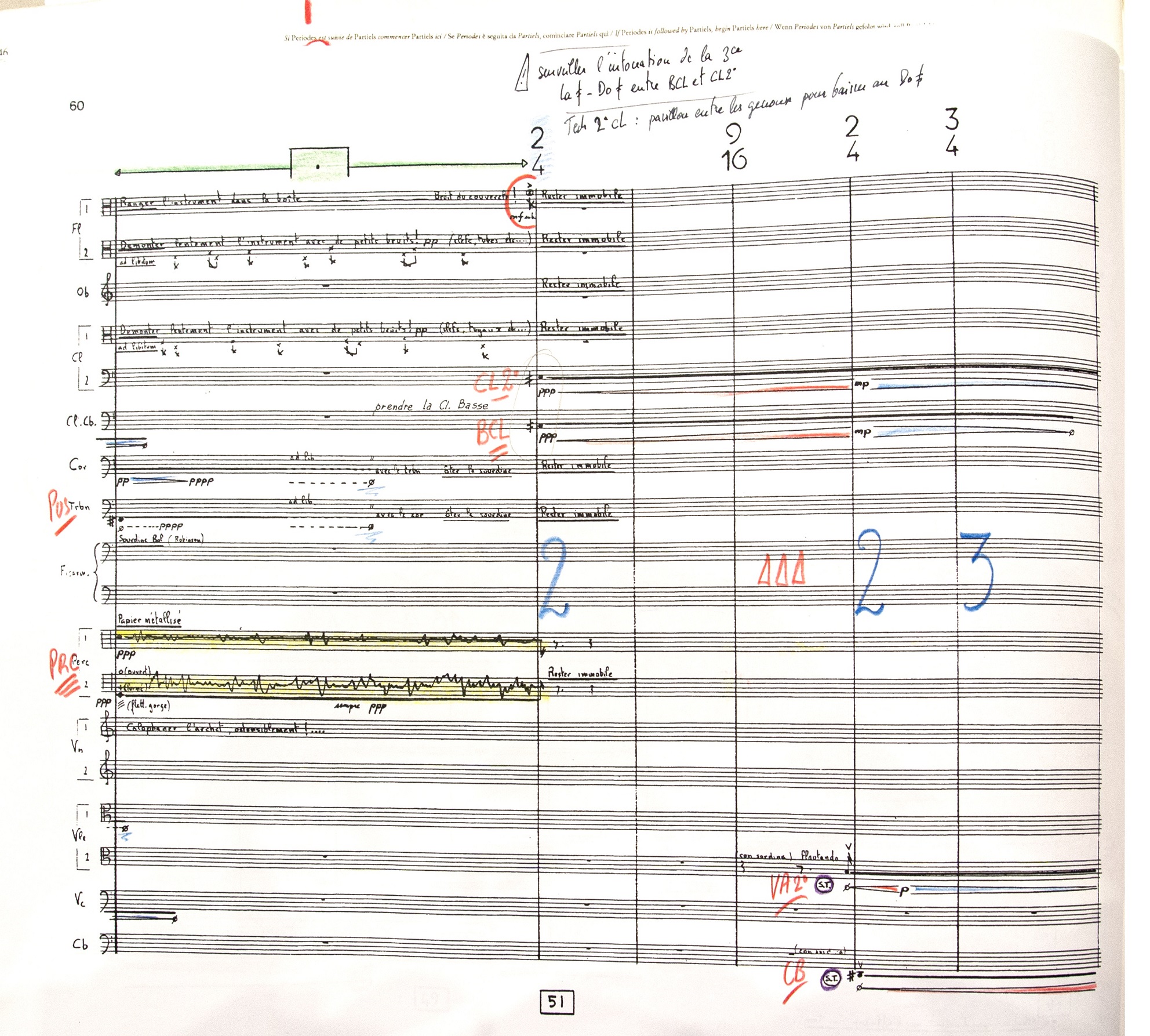

Since this is an aspect that depends on the balance of so many parameters including the space in which one plays, the relative dynamic indications (i.e. related to the specific context), as well as the individual sound characteristics of each musician developed through previous experience, only a couple of illustrative examples will be given in this section. The first example concerns the intonation of a minor third between Cl. 2 and B.Cl (A a quarter-tone sharper – C a quarter-tone sharper) as shown in Figure 6. This seemingly trivial step hides several problems of balance and intonation that can be solved by many ploys, some of them very practical ones such as using a mute on the bell of the instrument or resting the instrument on the knee (see Video 4). These are solutions that can only be found and best realised through practice and collaboration with one's musicians, in the common sharing of interpretative ideas.

Figure 6. Partiels, figure 51 [2443] – Annotations regarding the intonation of Cl.2 and B.Cl.

(Photo Ingrid Pustijanac, © Ricordi s.r.l., Milano, and Pierre-André Valade.)

[Download HD version (.tif)]

Video 4. “Partiels (51) — Grisey, Les Espaces Acoustiques (20 April 2016 afternoon rehearsal)”

(https://youtu.be/330_yJNFr1c, 19/11/2022).

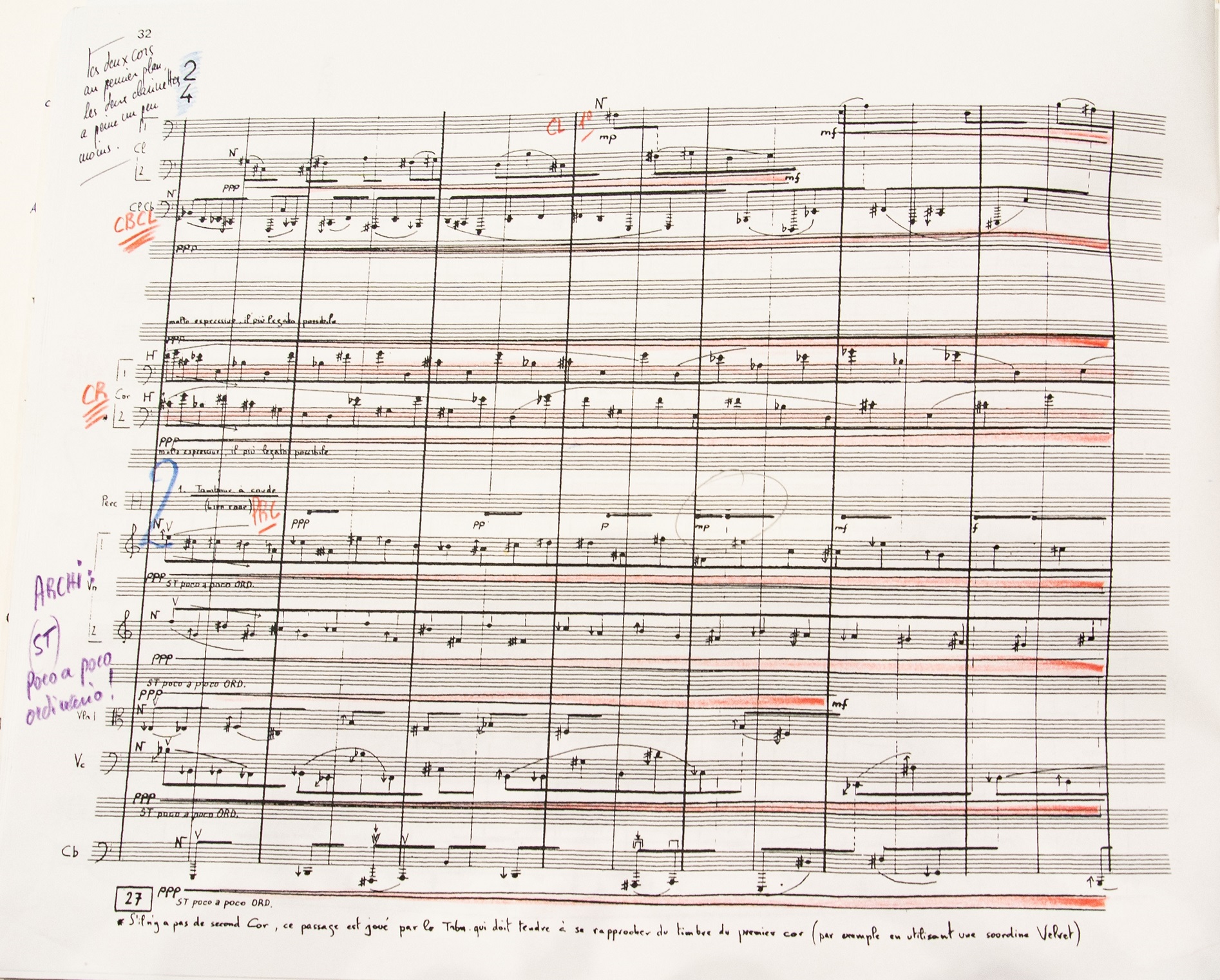

As a final example, we will illustrate a page from Partiels (at figure 27, Figure 7) as representative of another aspect as frequent as it is complex in Grisey's spectral compositions. This example concerns not only performance aspects but also a theoretical issue that is closely related to the concept of instrumental synthesis discussed at the beginning of this article and to the concept of artifice or metabole (as Grisey himself defined it). If we start from the assumption that in order to realise an effective fusion of timbres, instrumental synthesis must make use of sustained notes appropriately distributed and dynamically profiled across the registers, so that the articulation of the sound mass by means of glissandi, scales or arpeggios will consequently turn out to be a veritable artifice that only – under certain conditions – can lead to the desired result of timbral fusion. However, from the time he was composing Périodes and Partiels, Grisey experimented with new ways of articulating a harmonic spectrum through the very movement within the sound. This approach would later be developed to its full potential both during the composition of Prologue, in its essential and linear monodicity, and in the elaboration of the complex spectral polyphonies in the D section of Modulations, derived precisely from the neumes (archetypal Gestalt) of Prologue [1]. An early example of the delicate balance between the idea of sound as a model and the artifice of technique can be found in the section mentioned in Partiels (figure 27, see Figure 7). In this section, we are at the climax of the second process (figures 23-33), which from the first moment of rest (harmonic spectrum at figures 22-23) leads to the peak of inharmonicity (figure 28) expressed with very dense trilled gestures marked with fff dynamics throughout the ensemble, supported by the tremolo of the TamTam (“bag. de métal et mailloche”). The path toward density is articulated as a counterpoint between a Hauptstimme (the two horns, indicated in the score with the symbol 𝆦) and Nebenstimme (all other instruments, marked with the sign 𝆧). The melodic prominence of the two horns is emphasised even more by the indication “very expressive, as legato as possible (molto espressivo, il più legato possibile)”. In Valade's interpretation, this melodic gesture is supported by placing a little more emphasis on the part of the two clarinets. The annotation in the left corner of the page in fact says: “ the two horns in the foreground, the two clarinets a little bit less”.

Figure 7. Partiels figure 27 [2415] – Modelling the difference: Haupt- und Nebenstimme.

(Photo Ingrid Pustijanac, © Ricordi s.r.l., Milano, and Pierre-André Valade.)

[Download HD version (.tif)]

Commenting on this very passage (see Video 5), Pierre-André Valade explained that for the performance of this particular type of scoring, it is very important to be able to clarify to the individual musicians their role in a given context, for example whether they are part of a texture or have a more prominent solo part. Since scoring alone does not always get the context and role in it as in traditional scoring, the conductor's role is also to make each musician feel in the right place at the right time.

Video 5. “Textures, Spectral Polyphony, Proportional Notation (Interview with Pierre-André Valade, 8/11)”, 4:00

(https://youtu.be/I68OMdDC1fA?t=240, 19/11/2022).

A series of 'specific tips' for performers was already included in the conductor’s letter sent before the rehearsals. Amongst information on intonation, extended techniques, notational specificities and other issues, the conductor specifies passages relevant to individual instruments when they have prominent roles or are particularly exposed and not part of a denser structure.