1. The Beginning of the Journey

But first things first. The starting point is the score, and when it comes to Les Espaces Acoustiques, this operation is by no means a simple matter: whilst getting hold of the first four scores is no longer a problem (they can be easily purchased from the authorised dealers of the publisher Ricordi Milano [Universal Music Publishing Group]), the scores for Transitoires and Épilogue can only be rented [1]. Moreover, the spectral writing (as tutti divisi) that Grisey (and, more generally, the composers of spectral music) inherit from certain practices employed by Xenakis and especially Ligeti (cf. Atmosphères) means that these scores for large orchestra are of a size that makes the study (reading the score) and, even more so, the performance (i.e. the position of the scores on the music stand and turning the pages) very laborious [2].

Having overcome the obstacles in getting copies of the scores, we proceed with the study of the instrumental and orchestral ensemble, i.e. of the various instruments involved (paying particular attention to the percussion section and the correct identification of all the instruments required) [3]. This phase also includes the correct interpretation of the performance notes where the different performance techniques of the individual instruments are described. The construction of the colour palette begins. As can be deduced from the letter sent by conductor Valade to the orchestra, the first pieces (mainly Périodes and Partiels) use several extended techniques, the reason for which Valade states “I have chosen to give more indications for the first part of the cycle, as more peculiar ways of playing occur in that part, and leave the second part of the cycle with less indications, awaiting any questions you could have.” [4] These are techniques (multiphonics, tremolo, singing inside the instrument, etc.) that in 1974-1975 were still rather uncommon outside highly specialised ensembles, whereas today they have become a constitutive part of contemporary performance techniques [5]. The precision with which it is necessary to perform the complex sounds that can be achieved by means of extended techniques goes hand in hand with the control of the harmonic content, as both dimensions contribute to the construction of the sound's unfolding process, which alternates between phases of great harmonicity and those of greater instability and inharmonicity [6]. In order to express the harmonic content with as much precision as possible, Grisey uses a system that Valade describes to the orchestra: “The explanation of quarter-tone notation is rather unclear in the parts and looks very complicated, when it is in fact very simple and intuitive: Assuming that a # sign is drawn with two vertical lines and is two quarter-tones (a semi-tone) higher than the natural note, a # with only one vertical line (‡) will be only one quarter tone higher than the natural note, while a # sign drawn with three vertical lines will be three quarter-tones higher than the natural note, so one quarter-tone higher than the ordinary sharp sign. One reversed flat symbol (d) means a quarter-tone lower than the natural note, so a normal flat symbol (b) is a semi-tone lower than usual, and hence two reversed flats (dd) mean three quarter-tones lower than the natural note (one quarter-tone lower than the flat).” [7]

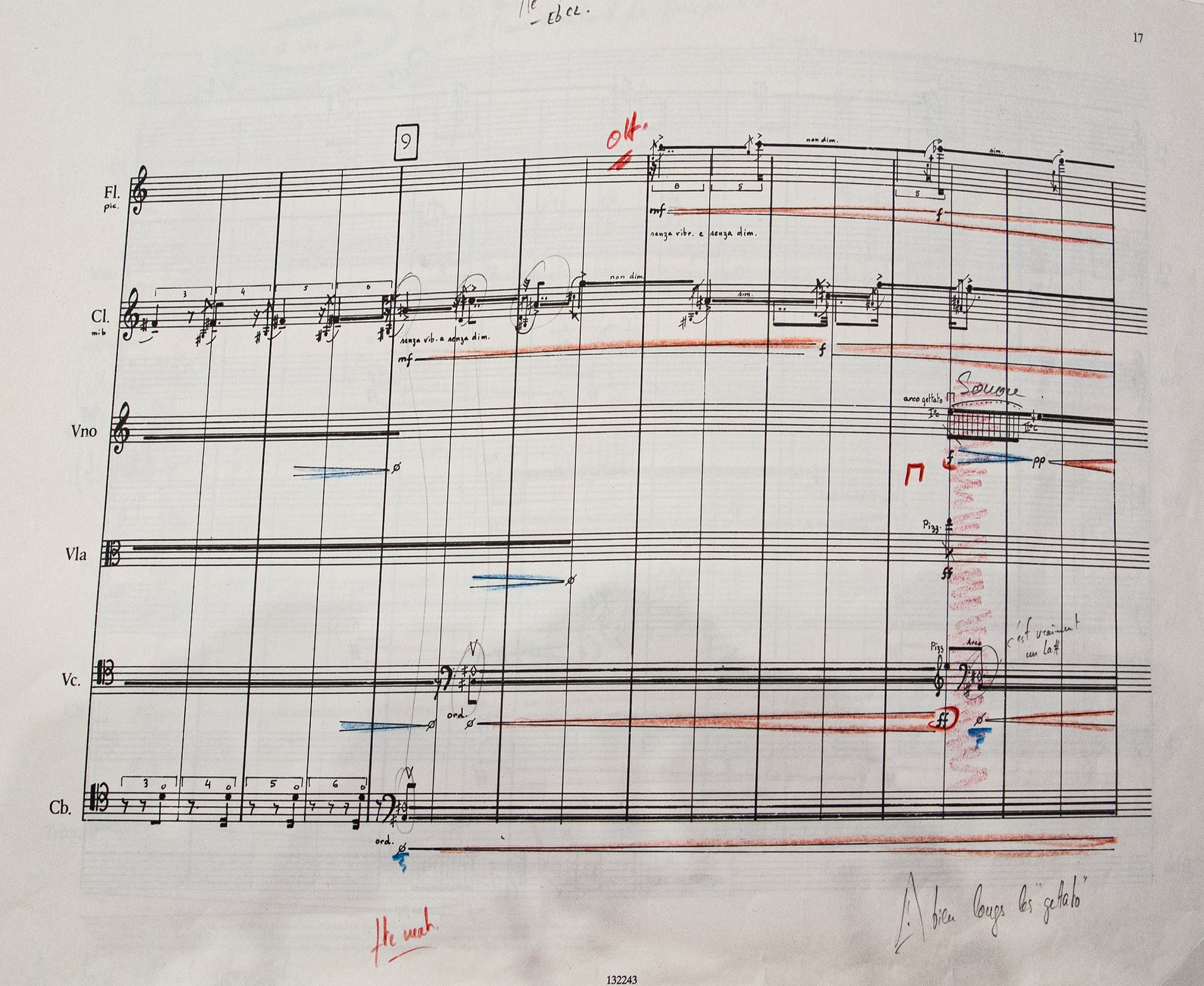

However, in contrast to the notational clarity of the harmonic content, there is the risk of misunderstanding the harmonic field due to two reasons: the first includes the presence of possible writing errors (oversights) of which the conductor must be aware in order to make the necessary corrections to the score and individual parts; the second includes situations in which the precise notation of pitches is in a context which makes it difficult to confirm the information. As an example of this second case, a passage taken from Périodes is cited which attracted the conductor's attention to the point of marking it in his score. On page 17 (Figure 2), after a harmonic field marked with an A a quarter-tone sharper (fourth harmonic in the double bass), a C a quarter-tone sharper (fourth harmonic in the cello), doubled by the clarinet in E-flat and by the piccolo, there then follows a new harmonic field corresponding to E natural (arco gettato sonoro in the violin) in which the cello plays an A sharp (again as a fourth harmonic) against an A natural in the E flat clarinet part. As the definition of new harmonic/ spectral content will take some time to settle, the conductor adds a verbal confirmation (c’est vraiment un la# / it’s really an A#) in order to deal promptly with any requests for clarification from the instrumentalist.

Figure 2. Périodes [2466] Valade’s annotation regarding the correctness of A# in the cello part

(c’est vraiment un la# / It’s really an A#).

(Photo Ingrid Pustijanac, © Ricordi s.r.l., Milano, and Pierre-André Valade.)

[Download HD version (.tif)]

Since the harmonic nature subordinated to processes of spectral evolution makes harmonic interpretation a difficult task, examples like this can be found in numerous other passages of the entire cycle and will not be examined here. Instead, the next part of this article will focus on the question of the notation of durations and rhythm, parameters that have largely modified the graphic and notational aspect of spectral scores.