2. Complex Sound Paradigms

In contrast to the fundamentally vertical dimension of the additive paradigm, there is the fundamentally horizontal dimension of a paradigm that can be described as granular, analogous to the synthesis of the same name. Whereas in the first case, the pitched notes aim at fusion by superposition, thereby undoing the conventional polyphonic stratification, in the second, the same goal is sought horizontally, by subverting the temporal limits of perception. A pitched note no longer simulates the sinewave, but the grain. As an electroacoustic technique, granular synthesis combines sounds lasting under 100 milliseconds by exerting a global control over them, intended or not to create an illusion of continuity, but in any case avoiding the smooth textures typical of the waveforms of additive synthesis, which are unsuitable for certain effects. While in the case of the additive function, the correspondence of instrumental sounds with sinewaves was restricted by their complexity, here it is the minimal limit of their duration that prevents them from spreading out in truly granular clouds. Such a function is, however, possible in the instrumental field, through the compression of the attacks, which is feasible up to well below the limit of 100 milliseconds for a monophonic instrument and can reach a few milliseconds for polyphonic instruments or configurations.

Even though granular paradigm does not have a comparable function to the additive paradigm in Les Espaces Acoustiques and in Grisey's work in general, and is not as explicitly conceptualised as instrumental synthesis, it should nevertheless be mentioned for the aggregative role it plays in the textural processes that are structured around different harmonic processes.

The following are the main ones, for which a detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this article. In Prologue, the trills and rapid stepwise descents gradually compress the initial melodic flow until it dissolves into glissandi. In Périodes, from figure 5 to figure 7, the process is reversed: the ascending glissandi gradually granulate and coagulate into distinct pitches. In Partiels, from figure 29 to figure 31, in the woodwinds, this happens again in the opposite direction: the stepwise descents accelerate to maximum speed (notated as barred stems) and, through the effect of unmetered shifts, produce a granulation whose compactness is reinforced by the aura of the accordion's sustained notes and the shimmering of the small cymbal. In Modulations, from figure 20 to 21, the descending melodic lines are gradually narrowed, then agglomerated until they become arpeggiated chords. In Épilogue, finally, the process of deceleration of the initial granular texture takes up the entire work.

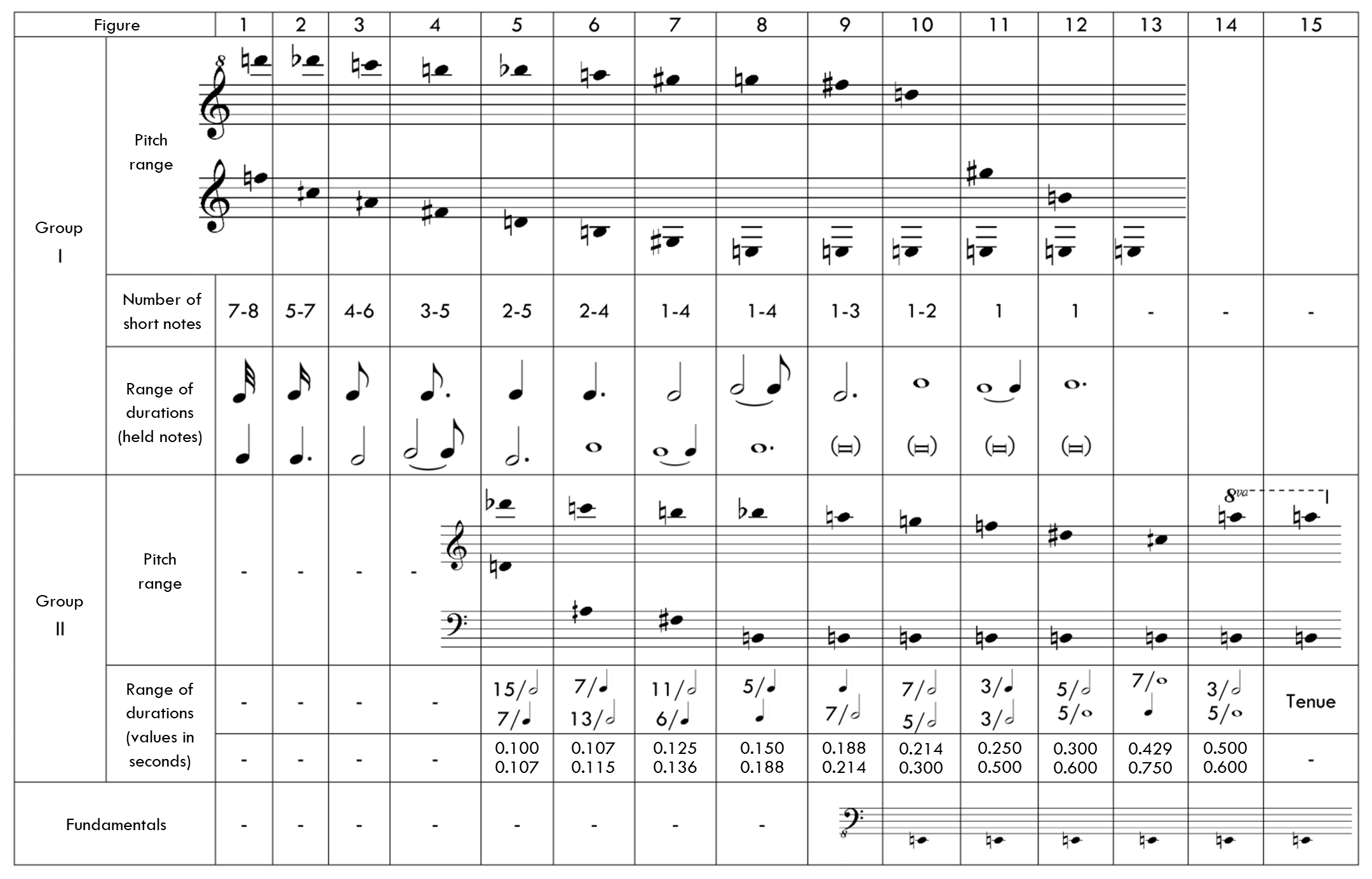

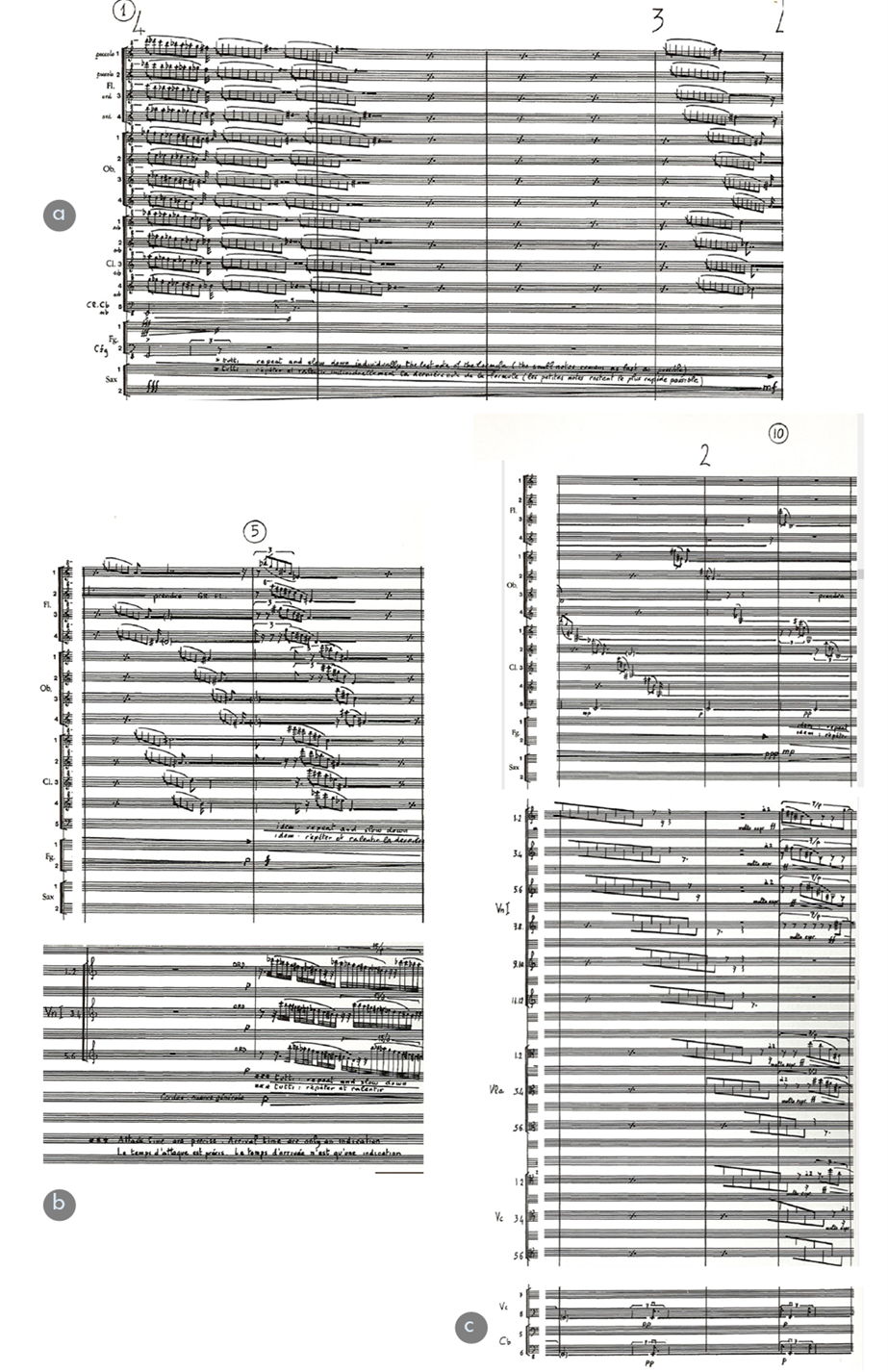

Let us examine this further using the summary table in Figure 2 and the extracts from Example 22. The instruments are divided into three groups: flutes, oboes and clarinets occupy the high and extreme high ranges; violins, violas, cellos and part of the double basses cover the entire low to high range; the other instruments play the fundamental in the extreme low range. The pitches of a harmonic field based on the spectrum of E are passed through in stages, starting from the high to the low register, that is, gradually approaching the fundamental. This progression is coupled with a gradual slowing down in time. The continuum begins in the first group alone: in Example 22/a, it is immediately apparent that it takes the form of a “cascade” of harmonics. These repeated, unmetered figures are played as fast as possible, which, taking into account the timing differences, produces a very strong granular effect. However, a duration is given for the arrival points, which, in the course of each sequence, progressively lengthen in time frames that are themselves gradually extended, while the number of short notes decreases.

The second group makes its entrance from figure 5 (see Example 22/b). The descending figures, which are metered and not sustained in a conclusive manner, are understood within the range of rhythmic values that are also gradually increased. It should be noted that within a section, these values are not enmeshed: even at high speed, the texture remains homorhythmic. Moreover, these durations themselves remain within the limit of the traditional note (100 milliseconds). From figure 7 onwards, the spread of pitches by the two groups reaches the harmonically characterised part of the chord, that is, a sparser zone, which reveals, in subtle touches, the spectrum of E. This eventually appears gradually, with the third group, between figure 8 and figure 10. At this point, the continuum has long since moved away from the granular thresholds (see Example 22/c) and begins a phase of disintegration that includes the disappearance of the first group at figure 13. Section 14, which is ambiguous, concludes the process by culminating in a large chord that is held at figure 15.

Figure 2. Relationship of durations to pitches in the process used in Épilogue.

Example 22. Three stages in the process used in Épilogue.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

Épilogue provides a textbook case of combining a spectral process with a rapid flux of notes, in terms of the transient and liminal qualities involved. On the overall scale of the process, the initial phase of maximum granulation is disrupted relatively early on, but all the elements work together to make any tipping point elusive; likewise, the transition from the harmonically saturated part to the spectral part of the chord is imperceptible.