1. Simple Sound Paradigms

Together with melody and polyphony, harmony constitutes the fundamental paradigm by which perception is structured by pitch. If we separate its elementary sound principle from its historical development in common practice tonality, as contemporary atonal harmony does, we can define the harmonic sound paradigm as a synchronous arrangement of distinct pitches. This paradigm is both the most specific feature of Western classical music and the point at which spectralism seems to relate most obviously to the historical legacy of classical music, via the concept of the timbre-chord. As its name suggests, it is a hybrid entity that can be defined as “a sound that, while not quite a timbre, is not quite a chord.” [1]. In Grisey's lexicon, however, this ambivalence seems to refer indifferently to several categories that are nonetheless quite distinct in his compositional practice.

For one thing, he already places a fusional emphasis on the approximation of the harmonic series on a piano – in other words, a conventional combination of tempered pitches without any particular timbral treatment:

Try it yourself on the piano: play a harmonic spectrum. Despite the tempered system, it does not sound like any other chord: it tends to merge (as for example in Territoires de l’oubli by Tristan Murail) [2].

Such a view is also found in some of Grisey's own works, such as Talea (1985), where the harmonic spectrum is played by the piano in tempered tuning. On the other hand, the technique of “instrumental synthesis” is developed, focusing on a much finer microtonal approximation and on the development of a set of advanced fusional composition techniques. The composer seems quite logically to regard the result as more integrated, but, although his lexicon sometimes equates fused timbres with simulated spectra [3], he is clearly aware of the impossibility for instrumental writing to be on a par with electronic synthesis:

Obviously, such fusion never takes place completely, and it is the tension between the resistance of the material and the musical writing that is of interest, which computer synthesis does not always have. The sounds produced by instrumental synthesis are hybrids, or mutants in a way; they are neither chords nor timbres, but a crossing between the two [4].

It would therefore seem that on the continuum linking the extreme polarities of a chord (individual components) and a timbre (fused components), there is not one, but at least two kinds of hybridisation: one that tends to focus more on the chord, that is, the timbre-chord, and the other that tends to focus more on the timbre, in other words, the instrumental synthesis. A better definition is needed, especially since Grisey's lexical usage seems rather vague; on the other hand, other spectral composers have developed rather different compositional principles of fusion (for example, Hugues Dufourt, who barely uses instrumental synthesis and yet aims for a high degree of fusion). How can we draw the line between the definition of harmony in the traditional sense and the beginning of its hybridisation? Are the chords found in Les Espaces Acoustiques chords in the normal sense of the word or timbre-chords?

A good idea at this juncture would be to consider the sound paradigm of a chord, which can be defined as the simultaneous combination of several pitches that can be perceived both as a totality and as a set of distinct units. Separating these units presupposes, firstly, the harmonicity of their respective timbres, the uniformity and stability of their dynamics and, secondly, the overall clarity of their arrangement, in other words to which degree they are perceived as complex combinations. If we accept the principle of equisonance of the octave – in other words, that octave doublings have zero harmonic complexity – and if we limit ourselves to the harmony notes, an average level of density can be envisaged, according to psychoacoustic data, as being comparable to what is found in tonal music, which rarely goes beyond four-part harmonic writing. David Huron concludes from his study of voice denumeration that, for musical textures employing relatively homogeneous timbre textures, “the accuracy of identifying the number of concurrent voices drops significantly at the point where a three-voice texture is augmented to four voices” [5]. More specifically oriented towards the perception of chords, the study by Josh McDermott and Andrew Oxenham concludes that listeners presented with artificial “chords” generated from random combinations of pure tones followed by a single probe tone are unable to tell if the probe tone was contained in the chord for chords containing more than three or four tones, at which point the tones seem to fuse together, even when the frequencies are not harmonically related as in a periodic sound [6]. These elements do not allow a clear demarcation to be drawn – but they are sufficient to indicate the beginning of a zone of ambivalence.

When defined in this way, harmony seems to be the least prominent simple sound paradigm in Les Espaces Acoustiques, far behind melody and polyphony. Its only occurrence is nonetheless remarkable: the melodic-harmonic texture of the horns throughout Épilogue take up the neumes of the viola in Prologue from the notes of the spectrum based on the fundamental E (Example 12). The pitches are clearly individuated, and although there are only two voices, the harmonic paradigm takes precedence over any sense of polyphony because of the homorhythm and the parallel movement that moves through the notes of an arpeggio like the effect of a traditional fanfare.

Example 12. Épilogue, figure 2 (detail).

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

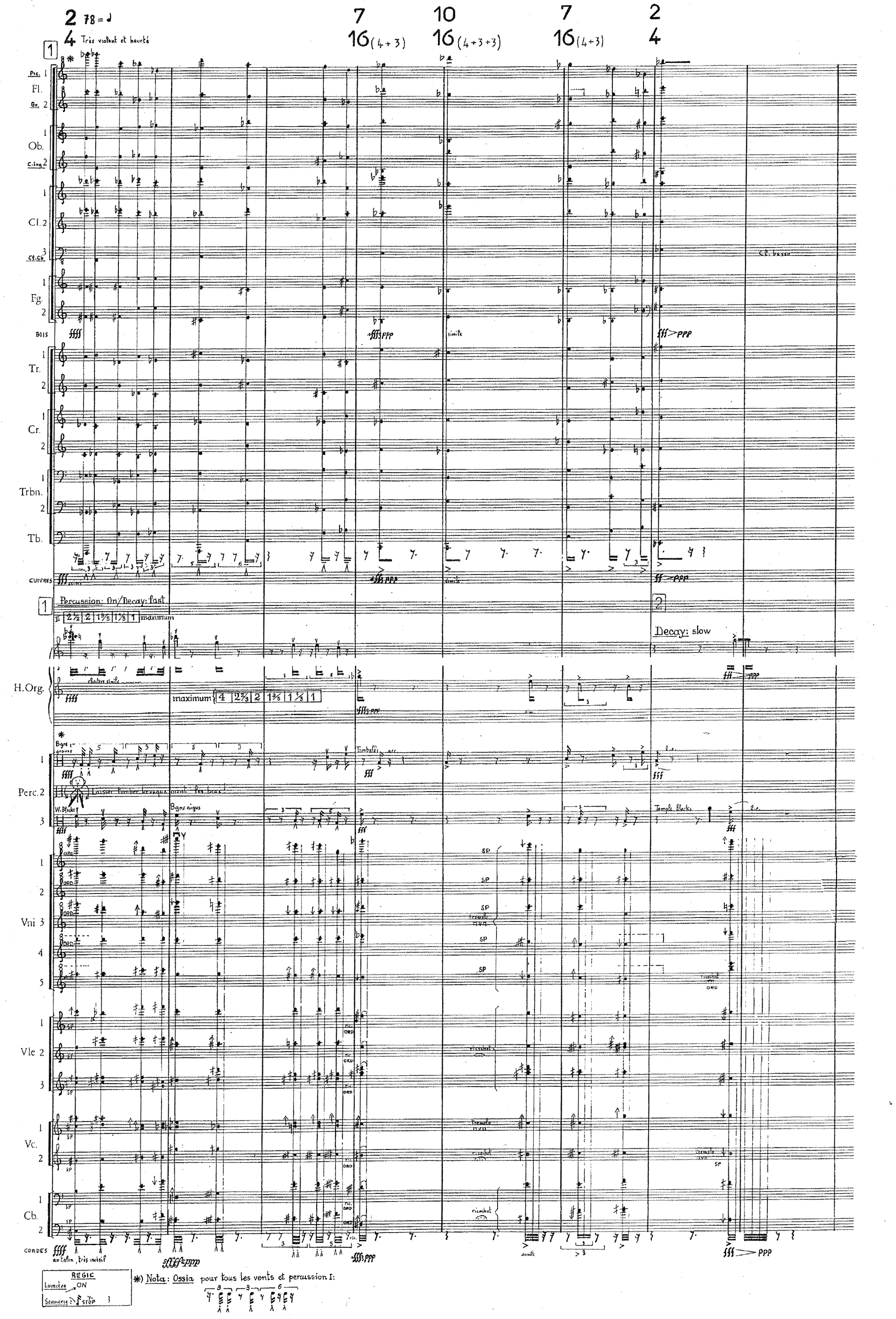

Within the cycle, the other configurations that come closest to being described as chords already have a degree of complexity that places them in the borderline region of the “timbre-chord”. Some notable examples of this are found in Modulations. From the very beginning of this movement in the cycle there is a rapid alternation of massive chords in the winds and strings respectively (Example 13). The influence of Messiaen and Varèse is evident, but the decisive expansion of Grisey’s approach to sound and compositional techniques is equally apparent. The perceptual definition of the chord is linked to the textural rhythm, whose restless liveliness contrasts sharply with the immersive stasis of Périodes and Partiels. The attacks are synchronous, the dynamics are forceful, stable and uniform. But the structuring function of the pitches is saturated by the extreme combinational complexity of aggregates often amounting to more than a dozen actual tones, whose density is further augmented by the “liminal” effect of microtonal proximities. The instrumental registers also play a role in the extreme higher and lower ends of the ambitus where, for various reasons [7], perception of the pitches is weakened. The arranging of certain parts of the chord into small clusters causes saturation of critical bandwidths [8]. Lastly, the inharmonic and noisy sounds of the percussion add a tangible timbral complexity to the ensemble. Some of the elements of the chord are de-functionalised on a strictly harmonic level and serve to vary its colour without changing its combinational nature, just as a spectral centroid would evolve.

Example 13. Modulations, figure 1.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)