1. Simple Sound Paradigms

Associated with the monodic texture of the viola solo, the notion of “melody” already features at the outset of Les Espaces Acoustiques cycle with Prologue and concludes it with the end of Transitoires and the end of Épilogue. However, Grisey removes the compositional intention of this setting from its more traditional context:

A melody can be perceived and memorised in two ways: by the notes that it contains or by the Gestalt (the shape) of the melodic curve. Prologue is entirely built on this second type of perception. [1]

The Gestalt refers to the neume which, in early medieval notation, defines the direction of a melody in terms of relative pitches. In his analysis of Prologue, F.-X. Féron notes that the sketches of the work explicitly mention the term and some of these medieval forms: clivis (two descending notes), scandicus (three ascending notes), climacus (at least three descending notes) [2]. Grisey goes on to say:

The melody is transformed in its essence, its Gestalt, its silhouette, though never on the level of notes, as its component pitches gradually move away from the initial spectrum and eventually reach into noise, moving through various degrees of non-harmoniousness. [3]

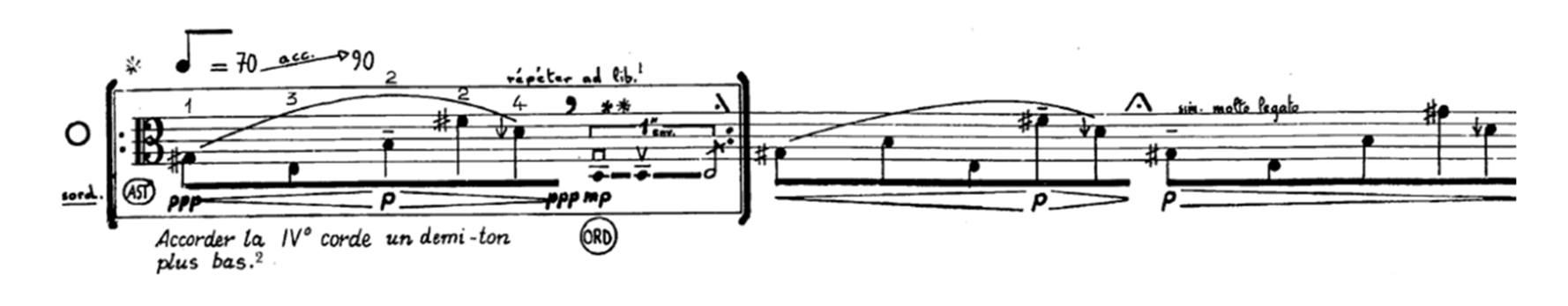

This example reveals an initial ambiguity about the actual role of the “level of notes”, in that, at the beginning of Prologue, the pitches indicated in the score are absolute and not relative. The neumes to which Grisey refers act here at a level of formal organisation, allowing the reiteration and variation of the contours of combinational structures to be worked through, but at the interpretative and perceptive level, these combinational structures are indeed melodic in the traditional sense of the term (Example 1).

Example 1. Prologue, beginning.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

Another ambiguity is the process by which the component pitches “gradually move away from the initial spectrum and eventually reach into noise, moving through various degrees of non-harmoniousness”. The spectrum in question is the E1 spectrum that underpins the compositional procedures of the whole cycle; but the word must be understood here in a quite different sense than in the following movements: at this stage it is not an actual spectral phenomenon, but a structural reference point guiding the organisation of the pitches – again, a formal organisation. The "harmoniousness" or “inharmoniousness” of this arrangement of notes refers to its abstract alignment to the pitch framework derived from the spectrum but does not change anything about the timbres actually perceived.

In other words, the neumatic formal process (relative pitches) shifts to a melodic formal process (absolute pitches), so that, contrary to what Grisey says, there is indeed transformation “on the level of notes”, which is based on a melodic sound paradigm: the sound densities in play at the beginning of Prologue remain conventional, both in terms of the viola's timbre (harmonics of specific pitches) and in terms of the arrangement of the notes, which is intelligible in its sequential development.

What begins to disrupt the melodic paradigm in Prologue is not the divergence of intervals from the abstract model of the harmonic series, but the dispersal of registers and, to a greater extent, the gradual subversion of the traditional levels of timbral density that condition the perception of pitches and their elementary relationships of continuity.

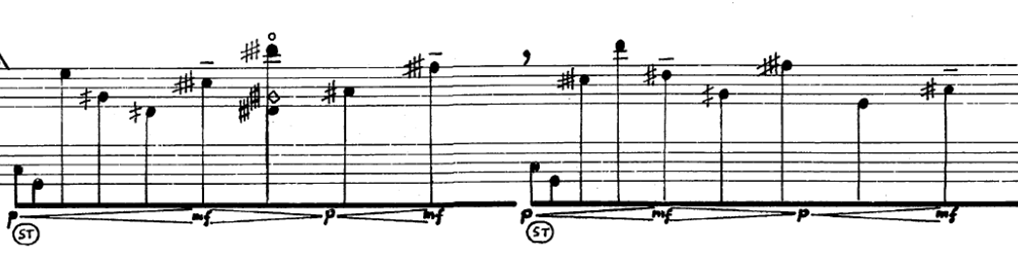

The first of these factors of entropy corresponds to the subversion of the melodic paradigm by a paradigm that can be described as disjunctive: this refers to a sound combination where the extension of the range and the discontinuity of registers prevent us from perceiving an organised sequence of distinct pitches. Such a paradigm has its historical origins in the pointillism of serial music, particularly in Webern; it is situated at the limit of simple and complex paradigms insofar as it disturbs the perception of pitches without subsuming them under a globally determined sound phenomenon. The second factor of entropy can be understood in terms of the concrete paradigm, based on the principle of the complexification of instrumental timbre. We will return to this point when we describe the complex paradigms, and for the time being we will limit ourselves to seeing how it contributes here to shifting the perception of absolute pitches towards relative pitches. Examples 2 and 3 show the joint effects of these two logics.

Example 2. Prologue, p. 2, system 5.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

Example 3. Prologue, p. 3, system 1.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

In addition to the weakening effect of the sul tasto bowing indication in the first example, the role played by the variations in dynamics (crescendos immediately followed by decrescendos, or "swells") should be noted, where the occurrence of increasingly pronounced contrasts breaks up the sound flow from the regular division of the note onsets. Perceptively, the relative importance of pitches is lessened in favour of purely dynamic gestures.

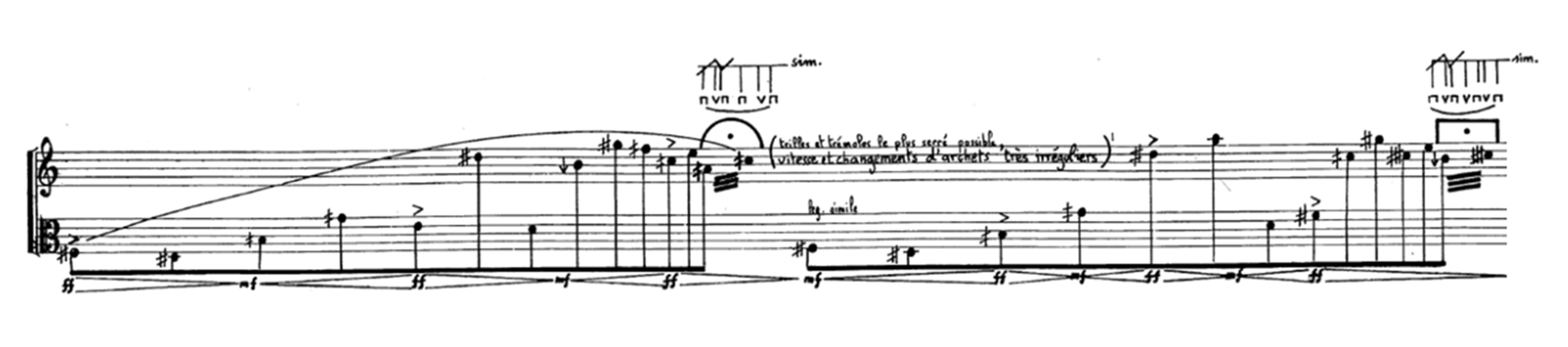

Along with the crush-bow sound, it is finally the glissandi, brought about by increasingly pronounced portamenti, that transform the melodic structures into continuous sound shapes. The neumatic principle then moves from the formal level (the abstract organisation of the composition) to the level of concrete sound paradigms: there are no longer perceptible pitches, that is, discrete coordinates that are determined by absolute pitches, but only relative pitch, that is, a moving of mutually dependent coordinates within the representational low-to-high acoustic space. As this motion is a glissando, we can more specifically speak of a continuous neumatic paradigm. After this dissolution of the melody into a gradually descending neume that can be likened to a bare gesture (Example 4), the last section of Prologue presents neumes of more complex articulation (Example 5).

Example 4. Prologue, p. 3, system 6.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

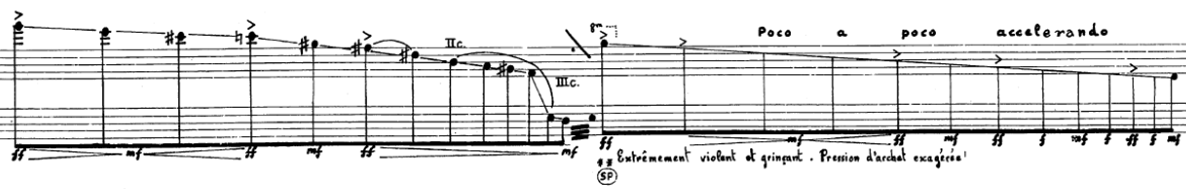

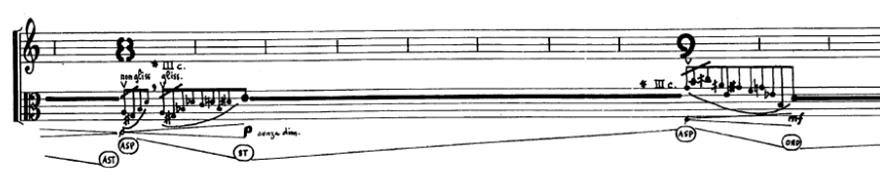

Example 5. Prologue, p. 4, system 4.

(© Ricordi s.r.l., Milano.)

There is a certain contradiction between the extreme notational determinacy of the pitches and their actual performative functionality. The continuity, speed and timbral complexity of the gesture make its execution and perception impossible to such a degree of precision, not only in practical terms, but also in paradigmatic terms. This paradox, however, is part of a notable characteristic of Grisey's style – and in many respects of certain aspects of spectral writing in general – which lies in the dialectical friction between contradictory paradigms. The tension is maintained by the greatest possible degree of irresolution between the indeterminacy of the neume and the determinacy of the melody, forcing, as it were, a commitment from the performer.