3. From Discourse to the Performative Act: Sound Fusion

The opening of Partiels is an ideal passage to examine how the performers engage with the notion of sound fusion on a practical level. For this, it is particularly interesting to consider an excerpt from the run-through of Partiels at the end of the afternoon session on 20 April 2016 (Video 6 [1]). The video excerpt begins at the very end of the previous piece, Périodes, which segues into Partiels seamlessly on “a spectrum of harmonics based on a fundamental E [2]”; it ends at the end of the sixth bar of figure 6. In this rehearsal passage, the conductor’s indications are given mainly by gestures, and also verbally on a few occasions, without interrupting the flow of the music. The music is based on a process of repetition leading progressively from a “harmonic spectrum” to a “spectrum of inharmonic partials [3]”, and it is particularly interesting to consider the performance adjustments that take place during the realisation of each “spectrum” – understood here in Grisey’s sense as a harmonic structure based on a E0 played by the double bass, repeated several times in varying rhythms and enriched by the progressive addition of other instruments. The first spectrum (from the beginning of the piece to figure 1) is here repeated three times [4], the first beginning with four occurrences of the double bass’s initial low E [5], the second with three occurrences and the third with four again (0:00-0:52). The initial realisation of this first spectrum (0:04-0:19) is carried out with minimal gestures: a beat of three is given only in the bars without a fermata and the conductor’s left hand is slightly raised on the fermata of bar 4. After this initial auditory evaluation phase, the repetition of the same spectrum (0:19-0:35) gives rise to a request to correct the overall dynamic decrescendo of bar 4: “Hold it, then diminish. Don’t diminish too soon, it’s too weak otherwise.” (0:26-0:35.) This instruction is accompanied by a different gesture from the conductor, aimed at showing the desired dynamics: this time his left hand is raised palm upwards and the whole body thrust forward, before a progressive return backwards accompanied by a lowering of the left hand. This request from the conductor aims to control the overall dynamic envelope of this spectrum, in order to avoid an overly marked diminution at the beginning of the decrescendo in bar 4. It probably serves a two-fold purpose: firstly, to control the duration under the fermata of bar 4, which is closely related to the duration of the sound’s fade-out, and secondly, to encourage a minimum listening time just after the dynamic high point, which would allow for a true blending of sounds, both acoustically and perceptually, in other words, a sensation of sound fusion – which requires a certain amount of time to take place. In the third realisation of this first spectrum (0:35-0:53), the orchestra seems to have responded to the conductor’s request. The conductor insists one last time (“Hold it”, 0:43), but in a less emphatic way.

Another condition for the phenomenon of sound fusion to occur is onset synchrony. As Moe Touizrar and Stephen McAdams point out, “the onsets of notes from the individual sources must be nearly simultaneous, within a time window of approximately 40 milliseconds [6].” This too is something the conductor seems to be trying to control, as shown by his comment to the double bass player during the third spectrum of the piece (figure 2, bar 3): “Downbeat of the 2/4 was a bit too soon.” (1:10-1:13.) Indeed, listening to the passage clearly reveals a misalignment between the respective onsets of the double bass and the other instruments that double this low E, in particular the trombone. The misalignment can be explained by the higher inertia of the brass in producing a sound and the consequent need for a string instrument to delay its attack very subtly in relation to the beat indicated by the conductor – the conductor thus leads slightly in advance. This difficulty of synchrony in the attack was already present in the realisation of the previous spectra (see, for example, 0:19-0:20 and 0:35-0:36). There is also the question of synchronisation between the double bass and the conductor, as can be seen in the third realisation of the first spectrum, during which the low E of the double bass is repeated four times – as opposed to three the second time –, causing a certain surprise on the part of the conductor, who indicates a somewhat anticipated entrance to the rest of the orchestra at this point (0:35-0:40). The best possible coordination between the conductor and the double bass in this type of passage also seems essential, as the other players in the orchestra are likely to use the double bass as an auditory cue, as one of the two flautists pointed out in their interview.

Finally, the end of this rehearsal excerpt highlights positive feedback from the conductor to the orchestra through a facial expression suggesting a certain satisfaction, accompanied by a nod of the head (figure 5, bars 5-6; 1:55-2:00). This gesture of the conductor seems to indicate a sound result that is more in line with the conductor’s mental sound image, whether it be the part of viola 1 with its particularly relevant unstable sound, or more generally the realisation of a particularly successful blend of sounds – and thus sound fusion – within this passage. The process of varied repetition characteristic of the beginning of this piece enables a two-way system of listening and interaction between the performers to be established, which takes shape as the music progresses. This aspect is part of a certain “didactic [7]” dimension characteristic of this piece and of the cycle as a whole.

Video 6. Beginning of the run-through of Partiels (afternoon rehearsal of 20 April 2016).

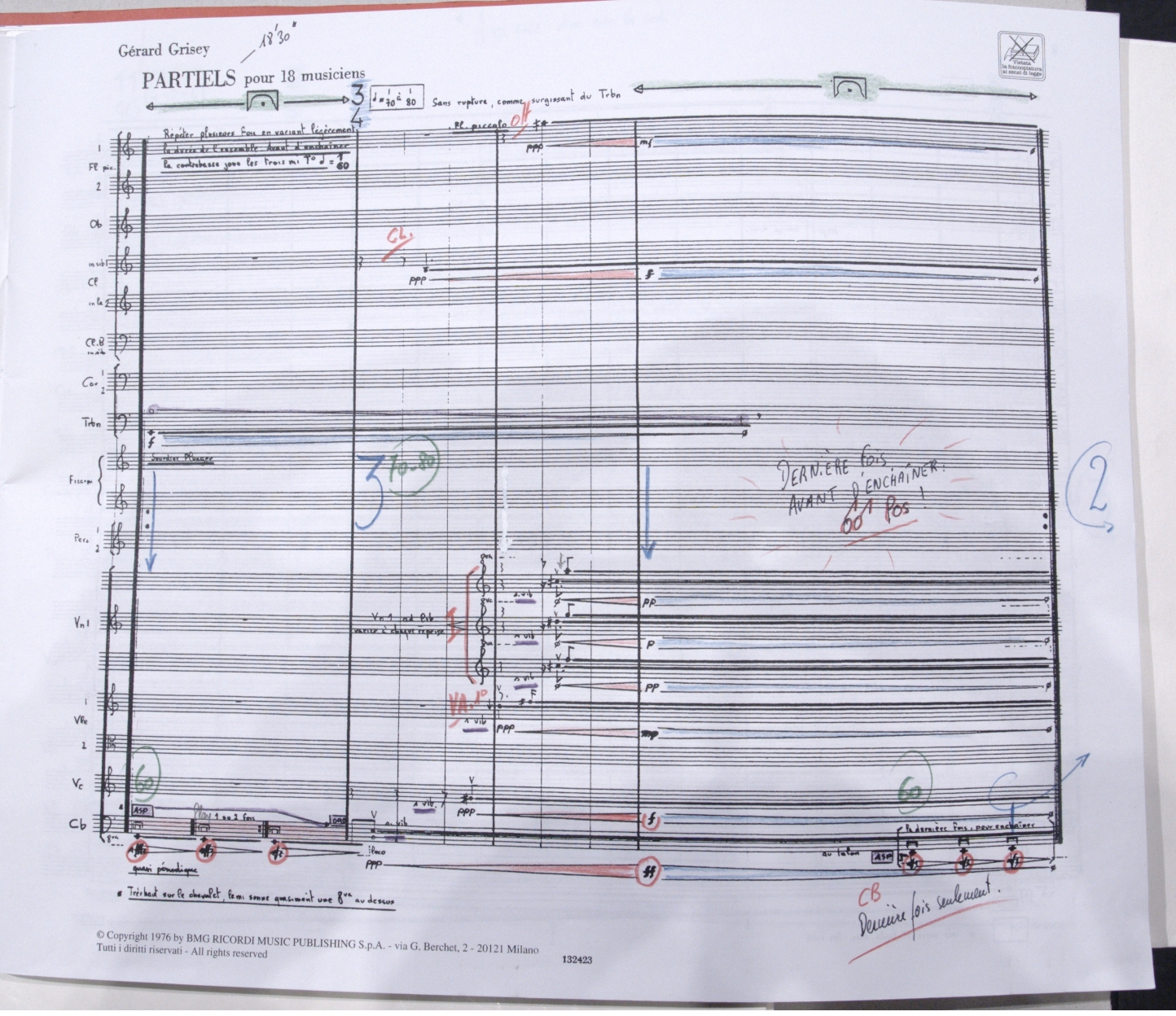

In addition to these thoughts concerning the performance of the beginning of Partiels from the perspective of sound fusion, it is also interesting to take a look at the conductor’s annotated score: a photograph of the first page of his score can be seen in Figure 3 [8]. Various graphic and written annotations appear in different colours: in green, tempo indications; in purple, indications of playing styles; in red, indications of strong dynamics, dynamic crescendos and instrument entries; in blue, indications of dynamic decrescendos and beats; and in black, some more personal additional written indications. This system of annotations highlights a parametric conception of the score, which is organised visually based on different coloured highlightings that represent points of attention for the conductor [9]. The idea of sound fusion and the issues involved in its instrumental realisation seem to be reflected essentially in the black marking in bar 4 that reminds the conductor to look at the trombone in anticipation of the downbeat at figure 1. The trombone’s timbre is in effect the structuring element of the various successive spectra at the beginning of Partiels. This marking also reveals the strategy implemented by the conductor during this tricky passage, which involves the simultaneous attacks of four instruments on the same note and which therefore requires the best possible synchronisation: to focus on one instrument in particular, like a section leader that the other instruments are required to follow. In addition, several other coloured annotations refer to elements of the score that are essential to produce a fused spectrum – for example, dynamics and instrumental entries –, but are not explicitly reflected in the conductor’s final gestures (Video 6), thus leaving a certain amount of freedom of control to the instrumentalists themselves, in a process of co-creation and shared responsibility for the sound result that is obtained.

Figure 3. First page of the score of Partiels annotated by Pierre-André Valade.

(Photo Ingrid Pustijanac, © Ricordi s.r.l., Milano, and Pierre-André Valade.)