Concepts like 'genre', 'style', 'form', 'mode' – and their equivalents – have been used for centuries in many cultures to classify music, by creating 'types of music' characterized by recurrences and similarities. One of the purposes of such taxonomies, according to a tradition originating from Aristotelian philosophy and developed throughout European music history (Fabbri 1981, 1982, 2007a, 2007b), as well as in other music traditions, has been to devise norms connecting the way music events are made with their meaning and social function; another fundamental purpose has been to facilitate discourse about music, by making it easier to recognize music events, describe, and 'point at' them.

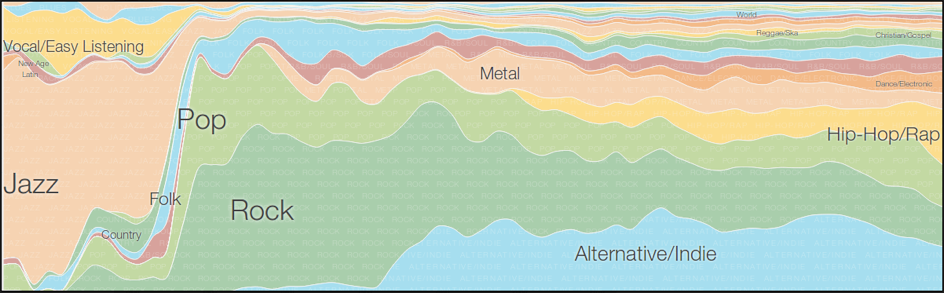

Such musical taxonomic concepts have a great impact on everyday music life. People choose a certain radio station (or listen to a certain web radio) because they like the selection of genres or styles it broadcasts; concert venues and clubs are specialized according to genre (their location in the urban space, the profile of their customers, the way in which the space is designed, and the acoustics of the halls are genre-oriented); record shops have shelves where similar music is assembled together (by genre), and record companies created genre-specific labels since their inception in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth century: their organization as corporate companies is genre-oriented (Negus 1999, Taylor 2014). As files with audiovisual content started circulating over the Internet, the need arose to attach digital 'tags' to them, to indicate their content and make it easier for users to find them. Soon, researchers in computer science started working on algorithms enabling the automatic recognition of music properties by the scansion of audio data, as one of the most challenging tasks in the Music Information Retrieval (MIR) research field; with the expansion of interactive features in so-called WWW 2.0, and the huge success of social media, MIR researchers started considering 'social tagging', 'folksonomies' (Lamere 2008), and other user-generated sources of information as a complement to the analysis of audio content (Sordo, Celma, Blech and Guaus 2008). Genre, style and other taxonomic concepts are now largely used in Internet, and big enterprises like Amazon, iTunes, Spotify, Last.fm, and others, improve their business by suggesting customers and listeners ('users', in Internet jargon) to buy or listen to music similar to previous purchases or listenings, by means of music recommender systems (Celma 2010). All musical taxonomic concepts play a central role in music making (see how 'form' and 'mode' are articulated in many different music cultures around the world), in music theory and criticism, in any kind of verbal communication about music. Music categorization contributes substantially to give music events a socially recognized meaning (Fabbri 2007a, Brackett 1995 and 2002, Tagg 2013).

Research on music categorization has been done in the domains of the Social Sciences and Humanities (musicology, popular music studies, ethnomusicology, philosophy, semiotics, anthropology, sociology), of the Physical Sciences and Engineering (computer science: for a survey and an extended bibliography see Sturm 2012), and of the Life Sciences (cognitive sciences and neurology). Scholars in each domain have acknowledged the existence of studies in the others, only to a limited degree, and – seemingly – more as a form of academic correctness than out of a need to understand more deeply the scientific problems involved.

Scholars in the Social Sciences and Humanities have of course acknowledged the paramount importance of Internet in the shaping and usage of current music categories (especially genre), but very few of them have dealt with the technical aspects of such usage (tagging, 'folksonomies', recommender systems, datasets and data mining, statistics). The lack of technical expertise leaves musicologists, media scholars, sociologists, etc., at the mercy of sensational news released on Internet, offering solutions to long-standing research issues. In January 2014 an article posted on the Google Research Blog proclaimed that according to 'data available on Internet' jazz was (or is?) the most popular genre in the 1950s (Cichowlas and Lam 2014).

An odd statement for a music historian's ears, considering that in the 1950s jazz was more and more becoming a genre for a niche of expert listeners, while rock 'n' roll emerged in that decade in the USA, and other genres became very popular at the same time elsewhere (chanson in France, for example). A closer examination of the dataset used for that research, would reveal that it was full of anachronisms (today's labels, like 'adult ballads', used retrospectively) and wrong entries (e.g. Serge Gainsbourg as a representative of jazz in the 1950s!). However, no music historian complained publicly, and the news was spread all over the mediasphere.

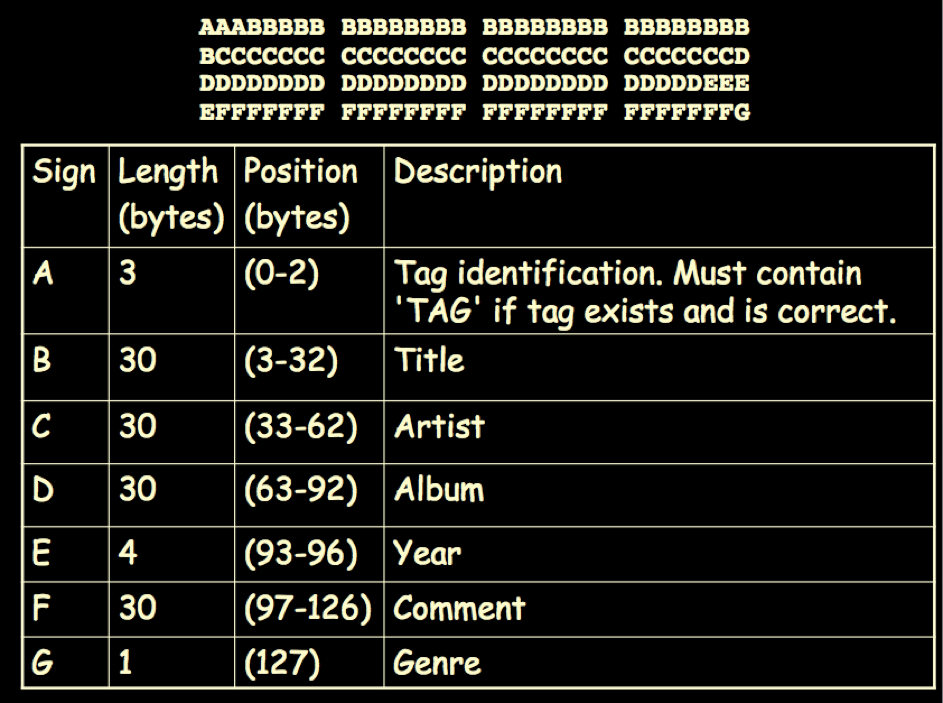

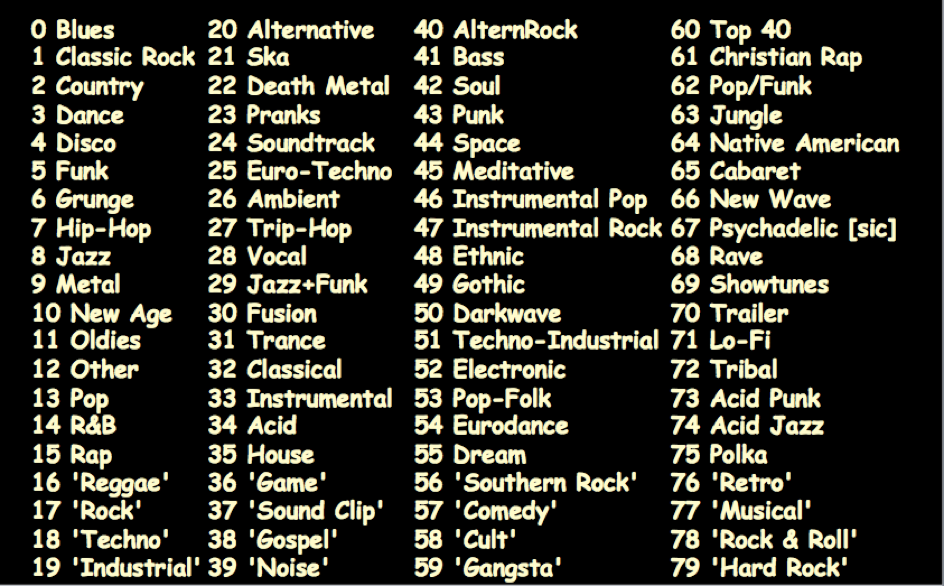

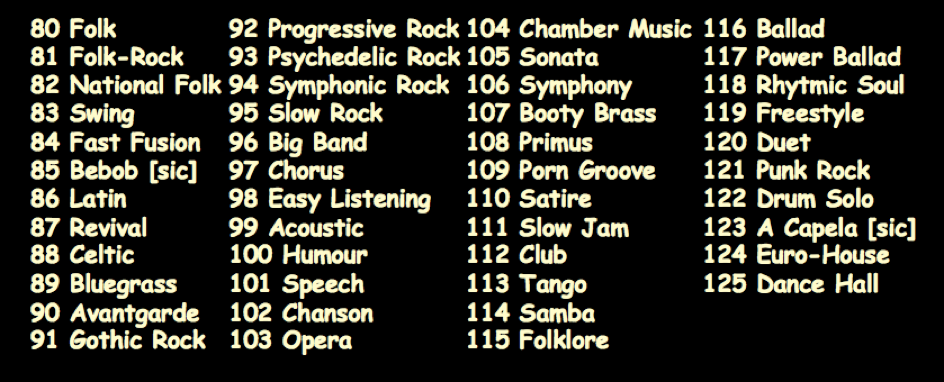

On the other hand, most scholars in computer science, especially in the MIR (Music Information Retrieval) field, seem to feel that their own musical competence, usually focused on the Anglo-American popular mainstream which dominates Internet usage in the West, be enough to build datasets and models for their research (which is necessarily concentrated on recorded music). From the first experiments (Tzanetakis 2002) to our days, the community focused on musical genres has compared different algorithms in the MIREX contest (Downie 2008, 2010) but always using static datasets with clear boundaries. Datasets are crucial for MIR research, and the choice is often limited by factors that are not under the researchers' control, like copyright ownership. Therefore, the fact that datasets are biased (which is the main cause for odd results like those mentioned above) is due to reasons that go beyond the musical expertise and/or taste of researchers. It must be said that many MIR scholars since the early 2000s have included references to musicology-oriented papers (see, for example, McKay 2004, Basili, Serafini and Stellato 2004, McKay and Fujinaga 2005, Guaus 2009), but most of them have limited themselves to picking up hints at very specific methodological issues. As a matter of fact, tagging protocols (ID3) used by some of the most popular applications (like iTunes) are now very old and inefficient: they are restricted to a limited number of genres (derived from the Anglo-American popular mainstream), obliging to categorize music not belonging to that mainstream as 'world music' without any distinction; they do not allow a correct management of chronological data, and the way pieces of classical music are described (usually referred to as 'songs', as this is the name for an audio file in Internet jargon) is simply disastrous. MIR researchers are not directly responsible for such a situation (commercially available music files are tagged mostly according to protocols developed initially in 1996 by a computer programmer with no specific music expertise), but the fact that no satisfactory standards have been proposed to date is disconcerting.

The ID3v1 protocol

The original list of genres in the ID3v1 protocol

Genres subsequently added by Nullsoft, the software house that developed WinAmp, one of the earliest mp3 players for PC and Mac

Cognitive scientists and neurologists have offered empirical results and theories that were very soon included in approaches to categorization by other disciplines (like musicology and computer science), with concepts like prototype, schema (see Lakoff 1987, Lakoff and Johnson 2003, and comments by Eco 1999), and others – e.g. mirror neurons (Rizzolatti 2005), which aren't directly related to categorization, but have left their mark on many music studies in the past ten years (Molnar-Szacaks and Overy 2006).

George Lakoff

At the moment, such research seems to be in a phase where cognitive scientists are more eager to give than to receive suggestions (see, for example, Levitin 2008), probably due to the complex nature of their experiments, the cost and bulkiness of the equipment involved (MRI scanners), and the fact that they are more often dealing with fundamental aspects of categorization, rather than with the very specific details of music categories.

Communities are a crucial concept in all disciplines involved in this research. It has been noted that although communities are included in the definition of other fundamental concepts – from 'meaning' and 'cultural unit' (Eco 1976), to 'genre' (Fabbri 1981, 1982), and even to 'nation' (Anderson 1983) – little has been done in order to give a detailed description of what it has to be meant by the term, whenever the concept is extended beyond its original formulation in sociology or anthropology (Kaufman Shelemay 2011). What kind of community is a 'virtual community'? Can the idea of an 'imagined community' be applied to the fans of a certain artist, or genre? Do communities overlap?