Let us consider, for example, the 1998 stage concert Eislermaterial, written for the hundredth anniversary of Eisler's birth. The pieces by Eisler are the raw material for this concert, but Goebbels' created a set of rules for the musicians of the Ensemble Modern giving a critical – in a political sense – meaning to the whole concert.

Above all, I am concerned that the musicians should assimilate the material; in the first instance because of the absence of a conductor – which Eisler would have very much welcomed! [1] – and which requires that the musicians are aware of what is going on, including what the others are playing. But then, such an awareness is made very much more difficult through the seating arrangement around an empty centre on the stage. Even the sections (strings, wind, etc.) don't sit together but everyone must be constantly vigilant, partly over a considerable distance … – which is very obvious for the audience too. Third, I included the musicians in the arrangement of the songs. First I gave all of them the piano part which we then distributed together. In the central section, there is then an additional improvisation in the treatment of the material. The condition here is that even with free improvisation […] the harmonic progression, rhythmical context or melodic work are never completely left out of consideration. [2]

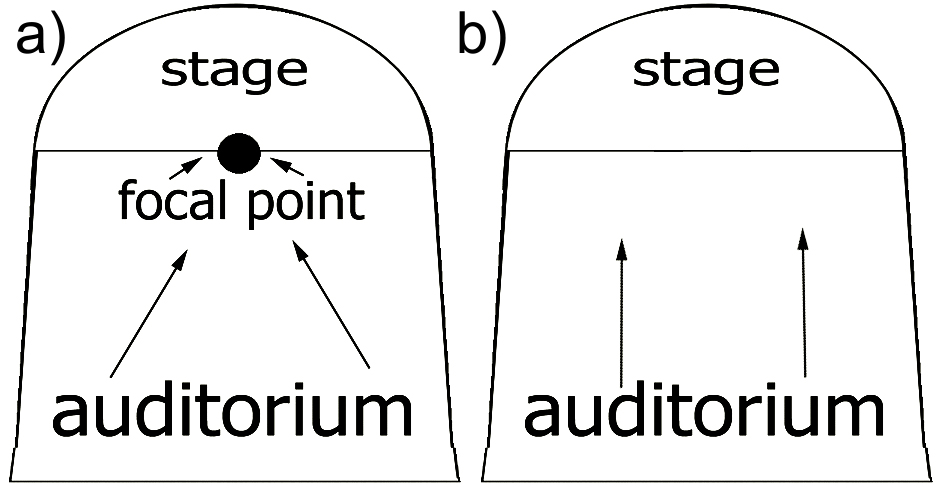

Theatrical perspective changes: the main focal point is not the conductor anymore, but the whole stage.

Figure 2. a) Conductor occupies the main position on stage [3]; b) the stage becomes the main focal point without a conductor, as in Eislermaterial (my rendition of figure a).

Figure 3. Eislermaterial on stage. No central focal point. [4]

Philip Tagg outlines an essential parallel regarding the relationships melody/accompaniment, figure/ground and conductor-composer-soloist/other musicians with the European bourgeois perception of the self, revealing what Eisler disliked about conductors and what Goebbels put on stage with Eislermaterial:

The usual position occupied by the most prominent figure (lead singer, main soloist, conductor, etc.) in live performance [is] the audiovisual focal point centre stage front, not backstage, or out in the wings. Centre front is also where the 'lead figure' is usually placed in the final mix of a recording (phonographic staging). This […] paradigm is similar to the figure/ground dualism of European painting since the Renaissance […] [5]

Seen in the context of a European history of ideas, the general change […] from contrapuntal polyphony to the melody‐accompaniment dualism not only runs parallel to a shift in painting from relative polycentrism to relative monocentrism; it can also be understood as a structural homology to the emergence of bourgeois notions of the individual […]. Put another way, the melody‐accompaniment paradigm, like the figure‐ground dualism of visual art, can itself be said to carry meaning in that it parallels the European bourgeois perception of the self in relation to social and natural environments. It also implies a generally monocentric socialisation strategy because the individual occupies ―as portraited figure, main character in a novel, or as foregrounded melody― a central position […] in the performance of human experience. It's 'me and the rest of existence', so to speak. This dualism […] pervades Western modes of representing relations between individuals and their social and natural surroundings […] [6]

Theatrically, in Eislermaterial cooperation between musicians is revealed, and conceptually, the absence of a leading/central figure and the critical behaviour the ensemble is forced to well represent Eislerian ideals, as in a Lehrstück, which, by definition, teaches also to those who play, not just to those who listen. But, apart from the political aspect of this staged concert, collective decisions and the necessity of a careful interplay are everyday practice for popular music groups all around the world. Goebbels gave a political meaning to what he discovered as a teenager.